Interview with Jan Poppendieck, Policy Director, NYC Food Policy Center at Hunter College

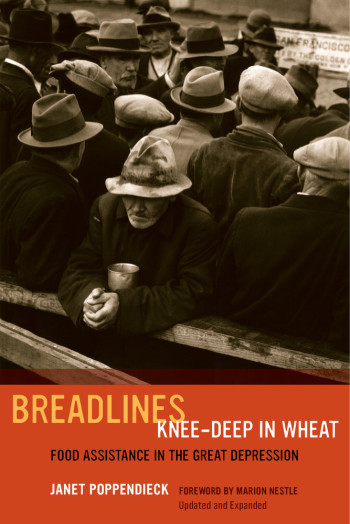

Janet Poppendieck, PhD, is Professor Emerita of Sociology at Hunter College, City University of New York and the Policy Director for the NYC Food Policy Center at Hunter College and the CUNY School of Public Health. Her primary concerns, both as a scholar and as an activist, have been poverty, hunger and food assistance in the United States. She serves on the Board of Why Hunger?, is the Vice Chair of the Board of Community Food Advocates, and is a member of the Leadership Council of School Food Focus. She is the author of Free for All: Fixing School Food in America(University of California Press, 2010); Sweet Charity? Emergency Food and the End of Entitlement (Penguin, 1999); and Breadlines Knee Deep in Wheat: Food Assistance in the Great Depression (University of California Press, 2014). Breadlines was recently re-released as a newly expanded and updated volume, updating the story of federal food aid in America.

Your 1986 book Breadlines Knee Deep in Wheat: Food Assistance in the Great Depression has been updated and re-released. Can you briefly talk about some of the new material and how it connects to the past release?

The original Breadlines is basically the origins story for domestic food assistance programs such as SNAP, school lunch, WIC and others. All of these programs are direct descendants of the surplus commodity operations of the Great Depression, and their history has been very much shaped by the circumstances of their birth. Basically the Roosevelt administration, faced with economic disaster in the corn belt, decided to forestall an impending glut on the hog market by buying and slaughtering millions of unripe baby pigs. The dramatic move proved to be a public relations disaster for FDR, evoking cries of “waste not, want not,” and charges that the administration was destroying food while people went hungry. The President moved decisively to organize a program to transfer farm surpluses to hungry unemployed Americans, beginning with the meat that could be salvaged from the pig slaughter. As a result, food assistance was located in the Agriculture Department, and overseen by the Agriculture Committees of Congress. This structure of authority helps to explain why food programs were serving low income Americans so poorly when hunger in America began making headline news in the late 1960’s, but it also helps to account for their relative success in recent years. Over the last several decades, food assistance has become a major part of the American social safety net, reaching far more people than “welfare” programs. Last year USDA administered more than 100 billion dollars worth of domestic food assistance, and one in four Americans participated in at least one of the Department’s 15 food and nutrition assistance programs. The epilogue to the new edition, which updates the story of federal food aid in America, analyzes the reasons for the relative “success” of food assistance compared with cash welfare, and looks at the changing context of food aid, and the challenges ahead.

The original Breadlines is basically the origins story for domestic food assistance programs such as SNAP, school lunch, WIC and others. All of these programs are direct descendants of the surplus commodity operations of the Great Depression, and their history has been very much shaped by the circumstances of their birth. Basically the Roosevelt administration, faced with economic disaster in the corn belt, decided to forestall an impending glut on the hog market by buying and slaughtering millions of unripe baby pigs. The dramatic move proved to be a public relations disaster for FDR, evoking cries of “waste not, want not,” and charges that the administration was destroying food while people went hungry. The President moved decisively to organize a program to transfer farm surpluses to hungry unemployed Americans, beginning with the meat that could be salvaged from the pig slaughter. As a result, food assistance was located in the Agriculture Department, and overseen by the Agriculture Committees of Congress. This structure of authority helps to explain why food programs were serving low income Americans so poorly when hunger in America began making headline news in the late 1960’s, but it also helps to account for their relative success in recent years. Over the last several decades, food assistance has become a major part of the American social safety net, reaching far more people than “welfare” programs. Last year USDA administered more than 100 billion dollars worth of domestic food assistance, and one in four Americans participated in at least one of the Department’s 15 food and nutrition assistance programs. The epilogue to the new edition, which updates the story of federal food aid in America, analyzes the reasons for the relative “success” of food assistance compared with cash welfare, and looks at the changing context of food aid, and the challenges ahead.

So, why has it been comparatively successful?

In the epilogue, I identify five factors that help to explain its size and scope, First , there is the link to Agriculture. Again and again, the Ag committees of Congress have voted to expand food assistance, thus expanding the share of the federal budget under their control, and giving them a massive bargaining chip in their interactions with urban members. Second, there is the role of business. Unlike cash, food assistance makes clear to vendors and suppliers their own stake in assistance to poor people. My social security benefits are indistinguishable from my cash income, but SNAP is readily visible to food retailers and to food manufacturers. Similarly, the farmers and food processors and manufacturers of lunch trays or chicken nuggets or half pints of milk that supply the school lunch programs recognize their interest in protecting these programs. Any form of relief “in-kind” makes allies of segments of the business sector. Third, there is the effect of devolution. In SNAP, especially, governors and mayors have realized that policies and actions under their control can help to bring federal SNAP dollars into their jurisdictions, and they have become active allies. Fourth , widely held core values are challenged by the specter of hunger in the land of plenty, and Americans have traditionally responded generously to appeals for food for hungry people. As historian Michael Katz has written of the SNAP program, “Food stamps escape the taint of welfare.” Hunger among plenty makes us uncomfortable, and all of our religious traditions urge us to “feed the hungry.” Food assistance has been able to draw upon this deep if sometimes confused strand of compassion. At the same time, food programs offer taxpayers a degree of control over the uses to which their funds can be put by restricting the aid to food. That is, they appeal to the part of the American psyche that is distrustful of poor people. And finally, there has been a long and persistent history of very effective advocacy. Skilled anti-hunger advocates linked in a network of national, state, and local organizations have monitored program performance, proposed new legislation, gathered support for reforms, organized opposition to cuts, and generally lobbied for expansion and improvement.

Unfortunately for poor people and their allies, all of these factors are currently threatened to some extent.

Can you explain the surplus food /hunger paradox?

The Great Depression was characterized by complementary symptoms of the underlying economic disorder. On the one hand, millions of unemployed workers and their families had no money to purchase food. On the other, crops were going to waste in the fields or at railroad sidings, with prices so low that they didn’t bear the costs of harvesting or shipping. Farmers were losing their homes and way of life to tax sales and mortgage foreclosures. Social commentators saw it as something new: want begotten by plenty. This was the situation reflected in the title–a Depression era slogan that held that “a breadline knee deep in wheat is surely the handiwork of foolish men.” Many people reacted viscerally to the waste of food while people went hungry, and when the food surpluses became concentrated in government hands, first through the massive wheat purchases made by the Federal Farm Board under Hoover and then by the surplus removal operations of the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, popular sentiment demanded action to feed hungry people. At a more fundamental level, however, the juxtaposition of want with waste was not a paradox—it was the normal workings of capitalism intensified by the depression—and by the perishable nature of farm products. Because it was widely perceived as a “paradox,” however, a small program that addressed both sides of the equation—transferring some of the unmarketable food to some of the hungry—did a great deal to relieve the political pressure.

Does past US food policy (e.g., food re-distribution programs) help or hurt current food policy?

That is a really interesting question. On the one hand, the link to agriculture was essential to the establishment of the modern Food Stamp Program, now SNAP, which last year provided assistance to 47 million Americans. The farm bloc in Congress basically traded its own support—or at least tolerance– for a program to feed poor people for urban, liberal support for subsidies for basic commodities such as wheat, cotton, corn and soy. That “log-roll” between farm interests and urban congress members has repeatedly protected food programs from severe cuts and block-granting. On the other hand, advocates of sustainable farming and critics of the farm commodity subsidies have argued that this horse-trading approach supports petroleum-dependent, monoculture based, toxic and climate-endangering, health-undermining, highly concentrated American agribusiness.

Many argue for moving food assistance, and especially the child nutrition programs, out of USDA—and out from under the farm interests in Congress. I don’t share that prescription. I fear that de-linked from agriculture, food programs would be vulnerable to the fate of Welfare programs in the mid-90s: entitlements would be replaced with block grants, and the real value of federal funding would be drastically reduced through a combination of cuts and inflation. Look what has happened to TANF (Temporary Assistance to Needy Families), the remaining federal welfare program for poor households with children. In 2011, TANF provided actual cash assistance to only 4.5 million people in 1.9 million families, compared to 31.6 million people in 9.8 million households with children served by SNAP (plus another 12.5 million in households without children). I would not want to forego the protection provided by the trade-offs with agriculture unless and until we build a real movement for reducing inequality and providing income security in the U.S., something that is certainly not “just around the corner.”

Fact Sheet:

What’s the last Food Policy book or blog you read: Graham Riches and Tiina Silvasti, Editors, First World Hunger Revisited: Food Charity or the Right to Food. I guess I should say I’ve “read in”it. I think the last one I read all the way through, cover to cover, was The Stop by Nick Saul and Andrea Curtis.

Current Location: Part time at the NYC Food Policy Center at Hunter College and the CUNY School of Public Health.

Education: PhD, Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University. MSW, also from the Heller School. B.A. in History from Duke University.

Favorite Food: This time of year it is Honeycrisp apples.

Website: Well, I actually have one: www.janetpoppendieck.com, but it is frightfully out of date.