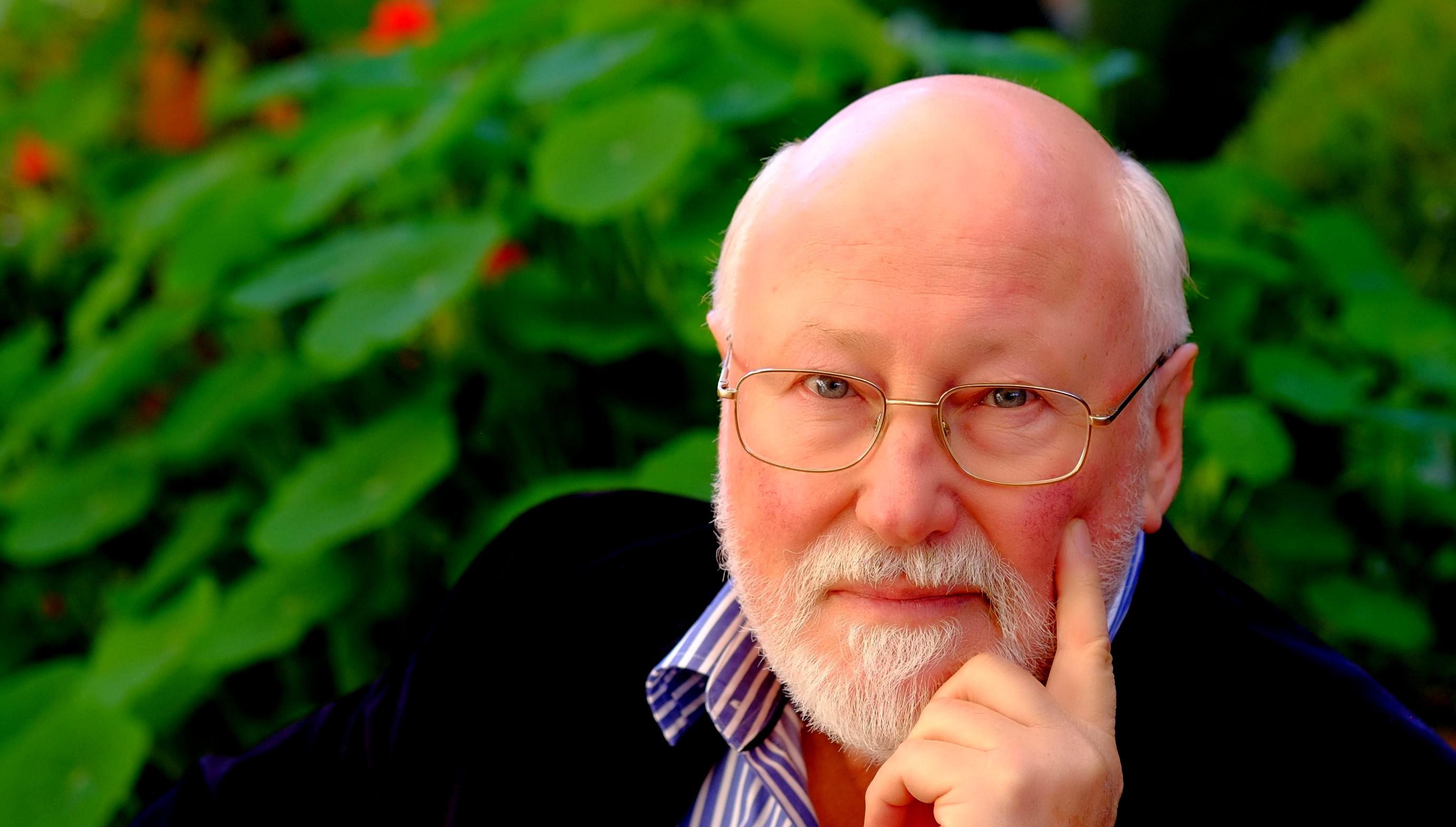

Julian Cribb is an Australian science writer who is particularly concerned with issues such as food insecurity, climate change, and species extinction that threaten our world today. He was previously the science editor for The Australian, a daily newspaper, and has published 12 books, including The Coming Famine, which has received international acclaim, and Surviving the 21st Century, which he has used as the basis for his blog about the existential crises faced by humans today. Julian Cribb’s work in environmental and scientific journalism has earned him more than 30 awards, including the Order of Australia Association’s Media Prize.

Julian Cribb (JC): Stone-age paintings show people fighting with hunting weapons as long ago as 17,000 years. Both the French Revolution and the Russian Revolution were driven by famines that unleashed citizen anger. However, the most important “food war” of recent times was World War II, in which the chief German war aim (according to historian Manfred Messerschmitt) was the taking of ‘“Lebensraum” or extensive farmlands to be settled by German farmers, from the Soviet Union. The issue was critical because of starvation in Germany during WW I, during which almost a million Germans died and everybody suffered, making it a live political issue in Hitler’s rise to power. Similarly, in the 1930s Japan planned to settle more than a million Japanese and Korean farmers in Manchuria and North China in response to the widespread hunger experienced during the Depression. Food was a weapon of war in both WWI and WW II. In more recent times, it has been (and still is) a major weapon deployed by the Saudis in their war against Yemen, which affects 24 million people.

FPC: History has shown us that food insecurity is not just a result of conflict but also a driver of it. It seems as if this book could have been written centuries ago and would still be relevant today. What makes the book so important for the times in which we are living?

JC: It is an unfortunate fact of modern media that the focus in any conflict tends to be on the actors rather than the underlying story. Thus, reportage of conflict tends to emphasize the political, religious and ethnic differences between the contending sides – rather that the factors that drove them into conflict in the first place. This presents a false perspective on the drivers of war. If one looks beneath these factors (which mainly determine who is on which side) we often find that the conflict began with disagreements over food, land and water, the absolute basics of survival for any society. When these are insufficient, people become frightened and angry and the population then fractures along political, religious or ethnic lines. In about two thirds of modern wars, disputes over food, land and water provide the spark that ignites the tinder. In theory, then, it is equally possible to avoid two thirds of wars by ensuring a stable, sustainable food supply for everyone – and this is a far more cost-effective solution than buying weapons. Food is a mighty “weapon of peace.” This insight is not yet widely appreciated in the defence or strategy communities and is a primary contribution of Food or War to the global debate about world peace and how to secure it. Remove a key casus belli by feeding everyone.

FPC: Do you believe food security should be a national security priority? Which, if any, national governments are adopting this philosophy and acting as such?

JC: I consider that food insecurity is an existential threat to the whole of humanity, and as such is a likely trigger for conflict (up to and including nuclear) within and between nations, accompanied by the unleashing of mass migration and refugees in the hundreds of millions. It is therefore a priority for the world–not just for nations but also for individuals. Presently, I do not see any national governments who display a firm grasp of the rising danger of food insecurity resulting from climate change or the fragility of the agro-industrial farming system and its resources. Supermarkets are mostly still full and nobody is panic-buying yet, so governments, driven by the present and domestic concerns, mostly put the issue of food scarcity on the back burner. Food security and agricultural policy tend to be second-order issues in politics compared with topics far more trivial that fill the media headlines today. But that could all change rapidly in the event of climate-driven crop failures, widespread drought or the collapse of individual megacities that have run out of water. A major food failure in Africa, for example, would sweep away most of Europe and probably the Middle East. A major food or water failure in the Asian subcontinent could go nuclear and thus damage harvests worldwide.

FPC: Climate change, overpopulation, deforestation and soil degradation, unsustainable use of resources–these are all global problems that require global solutions. International agencies and national governments certainly need to be involved, but can you identify other stakeholders who need a seat at the table to contribute to meaningful policy and change?

JC: These are both global and local problems, and require solution at all levels. In my previous book I pointed out that all solutions must be integrated across the ten existential threats – or else solving one will only make others worse. The stakeholders most glaringly excluded from policy discussion about the future of food are farmers (and fishers) and consumers. Their voices are muted and ignored compared with those of corporation as, governments and even NGOs. Farmers lack both political and economic power and are dictated to by huge agribusiness corporations whose focus is on profit, not food. The health of every consumer on the planet is being damaged by the modern industrial diet, which is overly contaminated by toxic chemicals at every stage and is causing malnutrition and diet-related disease on a universal scale. Yet, despite the fact that 66 to 85 percent of people living in modern society now die from a diet-related disease, the health of society appears a second order concern for most governments. A healthy diet is one way we can limit or prevent these diseases, which devour three quarters of the health budgets of most countries, and it is a far less costly solution than petrochemical “cures.”

FPC: Adopting a plant-based diet has received a great deal of attention as a promising solution. Do you think doing that can potentially lead us to create a more sustainable food system? What are the roadblocks, if any?

JC: As an agricultural journalist for more than 45 years, I tend to think that a balanced farming system involving both crops and livestock works best. If we eliminate livestock, we will end up with an unbalanced system almost entirely reliant on synthetic chemistry to prop it up. Certainly, industrialized intensive livestock systems like those in the US are unsustainable, unhealthy and cruel to both humans and livestock. But that does not make all livestock systems bad. Sustainable natural grazing in the rangelands, which cover 40 percent of the Earth’s land surface, is an essential component in a regenerative farming system, which in turn is part of a far greater sustainable and climate-proof food system, as described in Food or War. In addition, it would be a major contributor to the draw-down of vast amounts of carbon from the atmosphere and its sequestration in the soil. I am concerned, however, that there is a good deal more ideology than science or common sense in a lot of what is said about food nowadays. We need to rely upon an evidence-base, not a “meat bad/vegetables good” belief-driven ideology.

FPC: Part of the description of your new book reads: “This book is for anyone concerned about the health, safety, affordability, diversity, and sustainability of their food – and the peace of our planet.” One of your previous books, The Coming Famine, which was published in 2010, outlined similar themes, including the impending global food crisis. How have things changed over the last nine years? Are we in a better or worse place now?

JC: I began writing The Coming Famine in 2008, during the first global food crisis. At the time, I concluded that we could probably still feed the world by adopting a regenerative or ecological farming approach that repaired the obvious damage to soils, water, environmental and human health caused by the present system. However, as a science writer who has been reporting climate change since the mid-1970s, I have become increasingly concerned about the ability of agricultural systems to withstand the sorts of climatic and resource changes (such as access to water) now underway. Two degrees of global warming will be devastating for world grain production. Four degrees will probably completely destroy the farming system we know and love. It isn’t just the heat, drought, floods and pests; it will be their increasing frequency and savagery that will make conventional outdoor farming very hard to maintain. A farmer may have to cope, for example, with a drought, a heatwave, a locust attack and a flood, all in a single growing season. And how will farmers worldwide irrigate their crops and pastures when megacities and megaminers have taken their water? I believe there is a lot of misplaced optimism and false hope being peddled by corporate agriculture and its researchers, and we have yet to acknowledge the full gravity of the combined impacts of climate change, resource scarcity and ecological collapse on agriculture. Green Revolution-style techno-solutions will not work twice in such an environment. So, yes, we are in a graver situation now than we were a decade ago, with human food-demand still rising strongly and its resource base shrinking steadily.

FPC: In an article for Foodwise, you outlined four solutions to global food insecurity and stated that we need to start a World War on Waste. What would this look like? Who might be the winners and losers?

JC: Those ideas are developed further in Food or War. Over the past century, the human population increased four-fold, but our use of resources (water, timber, food, metals, energy, soil etc) has grown forty-fold. Put simply, this means that modern civilization cannot be sustained, and something has to change. One of the most effective changes, bringing widespread prosperity, would be to introduce a circular economy as described by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation – an economy where everything is used and recycled, nothing is wasted and there is no pollution. Applying this principle to food production, we see that the typical city uses and then throws away enough nutrients and fresh water to feed a city a third larger than itself. There is a vast new resource in the urban “waste stream” that can be turned into climate-proof food by a variety of systems described in the book that are now being tested by enterprising producers worldwide. Essentially, I see the future global food system as having three main pillars, each supplying about one third of human food needs – 1. Regenerative farming, which recycles and renews agricultural production, 2. Urban food production, which recycles water and nutrients presently being wasted back into nutritious, healthy and delicious new foods, and 3. Aquaculture, especially of algae and in the deep oceans. All of these can operate on circular principles and are thus sustainable, provided they do not pollute or damage the ecosystem in which they exist. They are all climate-proof or climate-resilient compared to current systems.

FPC: In that same article, you say we should be paying higher prices for quality food and supporting farmers more than we do. You concluded by saying there are many ways to ensure that farmers are paid a fair wage but you didn’t have the space to discuss specific strategies in that article. Can you expand on those strategies here?

JC: Farmers need a pay raise, or else the rest of us may find there is not enough to eat. You cannot sustain agriculture by constantly driving down the prices received by farmers for their produce while their costs rise interminably, which in turn forces them to overcrop, overgraze and overuse their farm. Agribusiness thinks you can, but agribusiness is wrong. It will create a desert, because that is what its economic system commands. If we are to convert an unsustainable farming system to one that regenerates the farm landscape instead of mining it and produces healthier, safer food for consumers, then there absolutely must be a monetary incentive for farmers to both take the risk of changing and make the necessary investment in regenerative systems. Without such a market signal, it will not happen on the necessary scale. Food today is the cheapest it has ever been in human history. It’s about one-third the price my grandparents paid for it. It is too cheap to last. There are a range of measures that can be taken to ensure the necessary change, including supermarkets’ realizing that screwing farmers is a stupid policy if they want a secure supply of food in the future. If there is a consumption tax, I believe it should be extended to include food and the revenue then remitted to farmers to restore their landscape, water, soil, wildlife etc. If consumers are helping to destroy the agro-ecosystem by paying too little for their food, it is only fair that they should pay for its repair and maintenance. For the very poor, welfare measures can offset the cost. Everyone else can buy one less flat-screen TV or smartphone per year – and pay the true cost of their food, not a price that is artificially and deceptively low.

FPC: On your blog, you wrote that the most destructive implement is the human jawbone. What did you mean by that? How can we be better stewards of the planet?

JC: Every meal you eat displaces ten kilos of topsoil, devours 800 liters of fresh water, uses 1.3 liters of diesel fuel, releases a third of a gram of pesticide and 3.5 kilos of climate-changing carbon.Multiply those numbers by 20 billion, and that’s how much damage the whole of humanity causes every single day, simply by the innocent act of eating. There has never been an implement as destructive of the Earth as the human jawbone. However, we can rapidly and readily eliminate this damage by (a) recycling all nutrients and water used in cities back into food systems (b) introducing regenerative farming to about half the area currently farmed and rewilding the remainder and (c) growing about a third of our food in the deep ocean, using algae as the feedstock for huge three dimensional fish and seaweed farms.

FPC: Also on your blog, you state, “Female leadership is one of the essential solutions to the ten huge existential risks” outlined in your aforementioned book, Surviving the 21st Century. Why do women carry so much potential for contributing to a more sustainable food system? How have you seen this play out in practice? Do you believe they are adequately recognized for their contributions?

JC: My book is about war as well as food. As a rule, women do not start wars, and they engage in them far less willingly and enthusiastically than men. Generally, they do not clearfell forests, stripmine landscapes, design new weapons of mass destruction, pillage the oceans or design new toxic substances to poison the planet. Sure, they benefit from those activities, but if women were in charge of these industries and governments, they would find ways to do all this in ways that are far less deadly and destructive to their children and grandchildren. Innately they tend to think more about the human future. Men have led throughout the ascent of human civilization, using many technologies that have had negative consequences when overused or badly used. If civilization is to survive, women must lead the next phase of finding safe, sustainable and healthy ways to do it, including ways to eat. Many women are emerging as leaders in regenerative farming, nutrition and dietary design, creating new food systems, products and methods of urban food production. This is both the Age of Food and the Age of Women.

FPC: Your writing educates readers about the harsh realities we face in our world today. The future can seem bleak at times, what with climate change, food shortages, and the toxins we are exposed to every day. Is there anything that gives you hope for the future of our planet?

JC: You never solve a problem if you do not first understand it. My four books on existential risk are all based on science from the most reputable and reliable sources that has been summarized so the average citizen can understand and share it. Indeed, the future looks bleak if we sit on our backsides and do nothing, or worse, deny it is happening. But the future also looks stupendously exciting, filled with promise for new jobs, industries, businesses, technologies, opportunities and foods, using that best of human instruments, our creative brain, sharing ideas and cooperating globally to make it all happen.

FPC: If you were given one million dollars to invest in the food system, how would you spend it and why?

JC: I would prefer you gave me $340 billion from the world’s annual weapons budget (20 percent). Then I would help design a sustainable global food system that would feed everyone, help prevent wars, pioneer the circular economy, lead by repairing the damage caused by economics t in order to make our planet resilient to climate and other impacts such as water and soil scarcity and thus take a major step toward ending the 6th Extinction. No miracles are necessary, just existing technology, the creative power of a billion farmers, foodies and inspired investors, universally shared wisdom and goodwill to all other humans.

FPC: Your bio states that your published work includes more than 8,000 articles, 3,000 media releases, and eight books. You’ve received 32 awards for journalism and are well esteemed in your field. What keeps you inspired to continue writing? What’s next on your literary list?

JC: As a grandfather, I want my grandkids to have a future. A lot of scientists and grandparents I have met of late think we are in the endgame of human history – and they may be right. However, in the evening of my life, I am inspired to do all I can, as a humble wordsmith, to guide humanity to the solutions and answers to its problems and its challenges. And food is among the greatest of these.

FACT SHEET

Grew up in: UK, world, Australia

City or town you call home: Canberra, capital of Australia.

Job title: Author. Fly fisherman.

Background and education: Degree in Classics (Homer). Newspaper journalist and editor. Director of communication for Australian national science agency. Small business operator in science communication.

One word you would use to describe our food system: F–ked. Or, if you prefer, Unsustainable.

Your food policy hero: Paul Ehrlich, because he was among the first to see where global overpopulation was leading us and the role of food in it.

Your breakfast this morning: Toast and vegemite.

Favorite food: Fresh veggies from my own small garden. Growing them makes them even more enjoyable and healthy. Everyone can do it.

Favorite last meal: Mung bean, pork, spinach and vegetable soup, a Philippino dish.