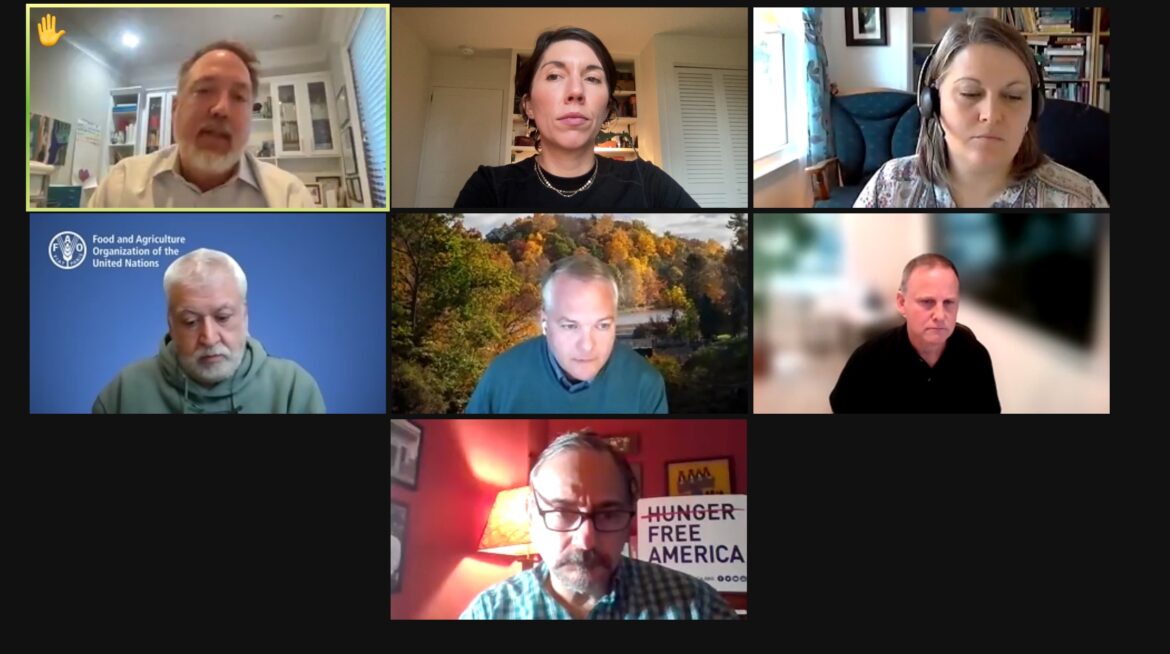

On October 26, 2021, the Hunter College NYC Food Policy Center hosted a panel discussion titled Measuring Food Insecurity. Panelists from various backgrounds and around the country were virtually invited to discuss the ways we measure hunger and food insecurity as well as the opportunities to improve the current systems and collect accurate measurements. Panelists included:

- Chris Barrett, PhD, Stephen B. & Janice G. Ashley Professor of Applied Economics and Management and International Professor of Agriculture, Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management, Cornell University, and Co-Editor-in-Chief of Food Policy

- Joel Berg, CEO, Hunger Free America

- Carlo Cafiero, PhD, Project Manager, “Voices of the Hungry,” Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- Alisha Coleman-Jensen, Social Science Analyst, Economic Research Service, USDA

- Trenor Williams, PhD, Founder & CEO, Socially Determined

Defining Food Insecurity

To kick off the discussion, moderator Charles Platkin, PhD, JD, MPH, shared the USDA’s definition of food insecurity: “the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways,” and asked the panel: “Do you all agree with that definition?”

“Those are definitions for society as a whole; there are slightly different definitions for household food security versus household food insecurity,” said Joel Berg. It’s important to distinguish between the mass famine that can occur in developing countries and the food struggles of households in developed countries.That said, however, the United States has “far more per capita food insecurity than virtually any other developed Western democracy,” he added. The definition of food insecurity is “imperfect in many, many ways,” but it is adequate for helping people understand it as a lack of purchasing power for food, distinct from hunger.

“Are we getting everything in that definition?” Dr. Platkin asked. Carlo Cafiero, PhD, jumped in to say, yes, that definition has everything. “But to have everything, it becomes a nightmare for the measurement, the assessment,” he added. Reporting on all the nuances is difficult to do in a way that doesn’t allow the facts and statistics to be twisted or misinterpreted. “Not all food insecure people are alike,” he said, and solutions vary based on other factors such as severity.

Alisha Coleman-Jensen added that “These are the conceptual definitions of food insecurity, from the Life Science Research office, and we know we’re not measuring all of those things.” Early in the measuring of food insecurity, the USDA realized that the addition of “socially acceptable ways” was necessary to add in order to specify that the definition refers to a lack of money or other resources that can be used to acquire food. She also emphasized the importance of an accurate measurement: “We need to have a strong measurement model that covers what we believe we can measure well.” Berg then elaborated a bit on the history of measuring food insecurity, stating that, for much of the first decade it was being measured, there was a subset of food insecurity described as “hunger.” During the George W. Bush administration, however, “hunger” was changed to “very low food security,” making it easier for people to conflate the two terms.

“Most things we really care about from a policy perspective: reducing poverty, improving sustainability, boosting resilience, reducing food insecurity. These are really important concepts, but as Alisha said, they’re just concepts,” said Chris Barrett, PhD. It’s therefore very important to have multiple measures, because you can almost never have one measure that encompasses all of these things.

Dr. Barrett then went on to bring up one factor that is often overlooked: “active and healthy life.” Many of the measures used today to quantify food insecurity were developed during a time when the primary concern was undernutrition. “But today, worldwide, that’s not the main problem…the main malnutrition problems are obesity and micronutrient deficiency,” he said. Therefore, we have trouble measuring it using measurements that were developed with undernutrition in mind. When we don’t check on the “active and healthy life” part, we inadvertently tailor policies to a smaller sector.

Trenor Williams, PhD, also brought up the concept of “nutrition security,” meaning access to healthy options, as an addition to the definition of food security, and spoke about the time component as well. “Some people, unfortunately, are food insecure for months if not years on end. And [for] some people, it is a very small, defined time.” He said it was important to consider the risk of food insecurity in one’s community, based on their own life. Including the community resources available for accessing food and individual financial situations that either help or hinder that access.

How We Are Currently Measuring Food Insecurity

Dr. Platkin asked the panel how food insecurity is currently being measured by the USDA. Coleman-Jensen explained that it is measured every December as part of the Census Bureau’s population survey that is also the source of poverty and unemployment statistics in the United States. The survey includes 18 questions about food security, 10 about the household and 8 about children. It is conducted by telephone (but also in person for some select groups) and has a high response rate.

Dr. Platkin brought up a study that used a social media survey conducted about food insecurity. The respondents, he said, were primarily White females, which is clearly not a representative sample. This began a discussion about the demographics of surveys, and how accurate they are. Dr. Cafiero warned that we should not to confound two concepts: “One is being able to capture the real reference population…and another is whether you’re measuring the right thing.” Surveys are conducted by asking people to report something as fact, not opinion. So the current model is a good way to access factual information in a simple, straightforward way. The alternative would be collecting data on what people actually eat, which is costly and inefficient.

Dr. Platkin asked whether we should be measuring food insecurity more frequently than once a year, such as once a month. Dr. Williams put a “healthcare lens” on the issue and spoke about the role that healthcare professionals can play in assessing food insecurity by measuring the daily risks for food insecurity within communities that are often missing from surveys. He said that, by taking into account such issues as food access points and non-food costs like rent, estimates of food insecurity rates could be calculated more frequently, but also made it clear that these types of measurements would be a complement to, but are in no way a replacement for the current survey model.

Dr. Barrett followed up by mentioning a research group he has worked with that attempts to use algorithms to predict malnutrition in the United States and around the world, but, “It’s incredibly difficult,” he said. Right now, tech and algorithms have the most potential to be used to identify subpopulations that are at risk, but, while algorithms are reasonably good at predicting poverty, “we don’t yet have predictive skills” for malnutrition. To train these algorithms to make predictions, survey data is needed. “The hope is that one day we can fill in the gaps between [once-per-year] high-quality survey data so that you have greater spatio-temporal coverage. You cover all the periods between expensive surveys. You cover communities you didn’t survey…That’s the promise of machine learning.” With algorithms and machine learning, you can use data about certain communities and time periods to project information about food insecurity rates in communities and during times when the surveys were not being conducted.

Referring to the huge costs associated with surveys, Berg said, “I’d rather use that [money] to reduce the problem than just further measure it.” He also mentioned the USDA’s monthly household poll survey, which measures food hardship. Hunger Free America will be releasing a report comparing that food hardship data with monthly SNAP increases, and Berg said that as soon as there is a significant increase in SNAP benefits, there is a correlated decrease in food hardship.

“There’s no question to me that the federal measures are undercounting food hardship,” he added. People always self-report lower rates of difficulty accessing food; they even self-report lower rates of SNAP enrollment than the actual numbers. A lot of people don’t admit to food hardship because they are worried about losing their children.

Dr. Platkin asked about whether surveys should include questions about the nutritional quality of the foods consumed. “The tendency of one measure to [include] everything under the sun is too much,” responded Dr. Cafiero. The USDA scales the ability to access food, not which specific foods every household is accessing, or even if the food is actually being consumed. Obviously, that alone is not enough, but it is helpful for understanding why some households are food insecure.

Coleman-Jensen further clarified what the USDA’s survey is measuring. “The food security measure is not a detailed measure of nutritional intake…it’s meant to measure if people can get enough to eat.” It’s very difficult to assess what people say about nutrition, but studies have shown that food insecurity measures do correlate with nutritional outcomes, food purchasing habits, and eating balanced meals. Dr. Platkin pushed back a bit about how to determine what is or isn’t a “balanced meal,” noting that the terms “balanced” and “healthy” mean different things to different people. Coleman-Jensen responded by agreeing that the “balanced meal” question is certainly not the strongest part of the survey, but said that it was a more useful term than “healthy.” When asked about balanced meals, “people got the concept that it was about a variety of foods,” she said. When asked about healthy meals, however, respondents spoke more about name brands and organic certifications, which is not what the survey is looking for. Dr. Cafiero then brought up ongoing research attempting to define “healthy” and its relationship with fruit and vegetable intake.

Berg added that “It’s important to move beyond what I think is a pretty simplistic understanding of ‘this is either good food or bad food.’” There are very complex reasons (economic, emotional, cultural, physiological, psychological) as to why people eat certain things at certain times.

Food Purchasing versus Emergency Food Relief

Alexina Cather, co-moderator, brought up some statistics from the USDA: in 2020, an estimated 89.5 percent of U.S. households were food secure throughout the entire year. “Something about this strikes me as not completely accurate, because we know how many households and individuals had to rely on food pantries and other forms of emergency food to feed their families. Should food [in]security estimates distinguish between households that are able to purchase their own food and those who have to rely on emergency food networks to feed their families?”

“It’s not that the number is wrong,” said Dr. Barrett. The question should be about agency — do people have the ability to go out and buy for themselves the food they want and need? The survey is not currently designed to answer the question of agency. Therefore, the results include the cumulative effect of some people being able to purchase their own food, the work of food pantries, food assistance expansion from the government, and other relief programs that indirectly helped people be able to purchase food, such as the eviction moratorium and expanded unemployment. “We have no idea which of those tools had which share of this effect,” he said.

Changing How We Measure Food Insecurity

When Dr. Platkin asked the panelists what they would change on these surveys, Dr. Cafiero indicated that we need to test additional questions to see if they belong on the survey and determine who exactly is responsible for continuing to conduct these surveys. It is also important to consider the “acquiring food in socially acceptable ways” statement, because different people might differ as to whether of not some food access methods (such as food pantries) should be considered socially acceptable. Furthermore, agency and access to food does not necessarily overlap with the severity of food insecurity.

When talking about designing research and measuring food insecurity, Berg says, “Don’t give the impression that we don’t know what causes it and what solves it.” Other data that is already collected on a monthly basis, such as poverty and unemployment rates, can serve as a pretty good proxy for food insecurity, he says. We ought to spend more money on solving it than studying it.

As an alternative to costly surveys, should we ask food pantries if there is an uptick? asked Dr. Platkin. “They will almost always say that there is,” responded Berg. “That’s probably one of the least accurate measurements.”

Asking people who are vulnerable these tough questions about food insecurity requires that people trust those asking the questions, said Dr. Williams. “I believe that there’s an opportunity from an access standpoint and from a cost-reimbursement standpoint to include the healthcare community in the assessment and understanding of people’s food insecurity — how they’re addressing that at a personal level, how it impacts their health, and their healthcare journey.” Leveraging healthcare provides an opportunity to get more data directly from people and a better understanding of what interventions will work best. Dr. Cafiero followed this up with a call to engage educators in efforts to measure food insecurity, because they often have the trust of their students.

Dr. Barrett then responded to Berg’s comment that we already know what causes food insecurity. While we certainly know that insufficient access to healthy, affordable food is part of the cause, he said, that is only a supply-side explanation. We need to further study the demand side of food insecurity. “I would personally speculate that the strongest features driving the 2020 food insecurity rates in the United States, that actually had it tick down rather than up in the midst of a horrific pandemic and economic disruption, were rent moritoria and increased unemployment [benefits].” We need to focus on people having livable incomes to purchase foods — demand — alongside access to healthy affordable foods — supply.

What Improvements Need to Be Made to Measuring Food Insecurity

Dr. Platkin asked each panelist to answer, in one or two sentences, “What should we be advocating for?”

Coleman-Jensen: “We just don’t have good survey-based measures of nutritional quality that are efficient and don’t have too much burden for respondents.”

Dr. Barrett: “We need to be careful about trying to cram everything into single measures…We need multiple measures.”

Dr. Williams: “We have to look at the supply side. We need to understand food resources. And we have to take advantage of the unbelievable data we have about communities, about populations, and about individuals.”

Berg: “We have to look at this in the broader context of people’s entire household budgets.”

Dr. Cafiero: “The food security measure that is used should be used as widely as possible and [reach] many people, and [it should] not [be] abused.”

Watch the entire panel discussion here.