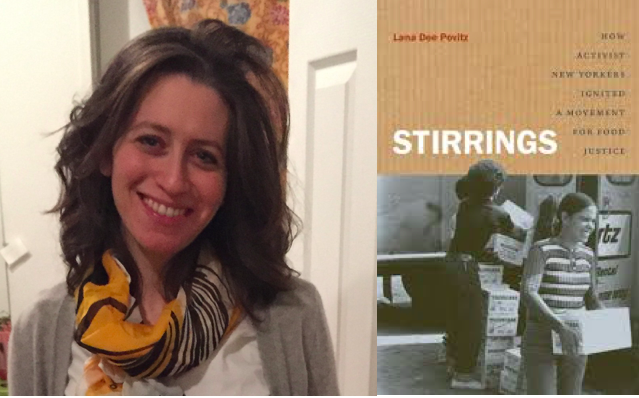

Lana Dee Povitz is Visiting Assistant Professor of History at Middlebury College. She recently published her first book, Stirrings: How Activist New Yorkers Ignited a Movement for Food Justice, which discusses how New Yorkers set the stage for a nationwide food justice movement in response to the poverty and hunger created by government cutbacks, stagnating wages, AIDS, and gentrification.

Povitz’s research and teaching focus on U.S. social movements and grassroots politics, women and gender, oral history and food politics. She received her PhD in U.S. History from New York University in 2017, and her work has received support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, the Mellon Foundation and the New York Council for the Humanities. She has published various articles on transnational feminism and urban food politics and is currently serving on the nominating committee of the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians.

Food Policy Center (FPC): You recently published your first book —Stirrings: How Activist New Yorkers Ignited a Movement for Food Justice. Congratulations! Why food activism? Was there a specific trigger that inspired you to write this book?

Lana Dee Povitz (LDP): Because everybody eats, food’s accessibility makes it relatively easy to get people to care about it. When people organize around food, it gives them a say over something that affects them multiple times a day, and it draws the participation of people who might not ordinarily think of themselves as “political” or “activists.” You don’t have to be “political” to care about hunger; you just have to know or imagine what it feels like not to have food on the table. I wrote this book because most of what was out there seemed very top-down. I had read quite a few damning studies of agribusiness and federal government policy–important, hard-hitting work– but where were the ordinary people who’ve worked to change things? I wanted to write a bottom-up, historical study of food politics that contained a lot of good stories!

FPC: What does food activism mean to you?

LDP: It means so many things! As I teach my students, food activism is never just about the food. It’s often a way of tackling larger systemic, and seemingly abstract, problems such as environmental destruction, white supremacy, and capitalism in a tangible way. I define food activism as any collective, not-for-profit effort that tries to make the food system more ethical, equitable, culturally appropriate, healthier or better in quality.

FPC: How do you see food as a tool for bringing people together and organizing people to build their collective power?

LDP: Food has the capacity to bring people together across lines of difference. Every time you offer someone something to eat, you have the potential to make a connection. When a volunteer for the New York City-based meal delivery service God’s Love We Deliver brought a gourmet dinner to someone dying of AIDS—a person who had perhaps been shunned by family, fired from their job, and scorned by society—it resonated on an extremely deep level. The existence of an organization like God’s Love gave regular people a way to express their care and helped build the critical mass necessary to start treating AIDS as the collective social problem it really was. Or, for another example, take a young mother, a recent immigrant from Puerto Rico, who spoke little English and had little formal education. When a meeting about test scores was held at her children’s school, she may not have felt comfortable participating. But if the meeting was about what her children should be served at lunch–suddenly, she’s emboldened to speak up and participate. The fact that food was a comfort zone for women allowed United Bronx Parents, an anti-poverty agency started in the 1960s, to build powerful campaigns to improve the food landscape for all New York City children.

FPC: The news is full of negative stories related to the food system: climate change and agriculture, sexual harassment in restaurants, food waste and cuts to SNAP benefits, to name just a few food-related issues. Do we need to reconsider the way we are organizing around food in order to be more impactful and to really move the needle on some of the food system’s most pressing problems?

LDP: I think we probably always need to be reconsidering how we are organizing, to make sure we’re keeping things as fresh and strategic as possible. One of the most important things food activists can do is build strong, broad coalitions, which often involves supporting the work of other groups that are not exclusively or directly “about” food–worker centers and unions, immigrant rights associations, environmental direct-action groups.

FPC: In your book, you talk about dominant social values. What are dominant social values and what does food have to do with them?

LDP: We absorb dominant social values just by living in the world: we encounter them on highway billboards and subway-car ads, on the news, in a presidential state of the union address. The key thing about dominant social values is that they affirm existing power structures. One example I discuss in my book is “personal responsibility,” the idea that, as free agents, we are each responsible for our own wellbeing. Within this paradigm, poor people individually must seek education or job training to escape poverty rather than depending on society collectively to transform economic inequality by mandating higher wages, protecting workers, or redistributing wealth. How does this relate to food? “Personal responsibility” devolves the responsibility of distributing and regulating food to individuals. School lunches, for example, become the parents’ concern rather than schools’. Pesticide-free food becomes a boutique consumer preference rather than a public expectation that government should monitor industry. This dominant value overwhelmingly privileges those who already have money, time, education, and access.

FPC: You’ve studied numerous community-based advocacy efforts. What are some of the keys to successful, sustainable political work?

LDP: Successful, sustainable community-based efforts offer people many different ways to express their support. It’s not only about getting donations and petition signatures, but about allowing people to share whatever else they may have to offer: time, connections, resources such as trucks, free printing, food, and skills, such as videography, graphic design, or social media support. Successful, sustainable political work also requires commitment from leadership to stick around. It’s difficult to have an impact without stability and institutional memory. Finally, strong relationships are one of the least discussed but most important parts of community-based efforts. The real strength of grassroots projects, especially when made up of volunteers, exists in the bonds among members. Feelings of connectedness may not be what brings people into food-advocacy work, but it is very often what keeps them there.

FPC: The leaders of the food movement you highlighted in your book were mostly female. Was this more than a coincidence? How does gender impact activism?

LDP: We live in a culture where the majority of caregiving work has been assigned to women. This is a mixed legacy: a source of pride and satisfaction, yes, but also a burden, especially for low-income women of color who have overwhelmingly worked in poorly remunerated positions that lack benefits. But despite this legacy, and even perhaps because of it, food has been an accessible medium for women’s political participation. Food activism has been one of the few spheres in which women’s authority is less likely to be challenged. But while women have dominated numerically, it would be a mistake to overlook the contributions of men. In most of the organizations I examined, men did take on key roles, sometimes even in leadership.

FPC: Stirrings talks about how New Yorkers set the stage for the nationwide food movement. Can you talk briefly about the different approaches New Yorkers took: organizing school lunch campaigns, lobbying city officials, establishing coops and more. In your opinion, was one approach more impactful than the others, and, if so, which and why?

LDP: The approaches fall into two groups: those that worked in relationship with the state and those that worked privately to accomplish their goals. United Bronx Parents, an antipoverty agency founded in the 1960s, exemplifies the first approach as it pressured the city government to improve school lunches and made use of federal money to provide free summer meals for children. Similarly, the Community Food Resource Center focused on mitigating the fallout from government-sponsored austerity programs through a combination of direct service and advocacy. The other two organizations I examine, the Park Slope Food Coop and God’s Love We Deliver, show the amazing things that can be achieved when people volunteer. Although the two nonprofits had very different missions–the former, a countercultural food cooperative seeking to provide high-quality, low-cost food to working members, and the latter aiming to ease the suffering of those sick with AIDS–both groups successfully used food as a way to build community, an alternative to alienation or abandonment. I don’t think one approach is necessarily more impactful than the other. It depends on the goal. But I do believe that government should guarantee a basic standard of living for everyone.

FPC: Where do you think the food justice movement stands right now? What are the next steps?

LDP: I’ll leave this to the people on the ground. Some excellent NYC-based groups to listen to include Community Food Advocates, the Worker Justice Center of New York, Farm School NYC, Street Vendor Project, and Hunger Free NYC. And nationally, I am always thrilled to follow the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, Farmworker Justice, and Restaurant Opportunities Centers United (ROC United), and the work of the stalwart Food Research and Action Center (FRAC).

FPC: In terms of activism, we often talk about a top down or bottom up approach. Do you think one is more effective than the other? Why or why not?

LDP: We absolutely need both for lasting progressive change to occur–and ideally top down and bottom up efforts should be coordinated. People should work where they will be most effective. Some people have a better skill-set for legislative or policy organizing; others shine at the grassroots, making connections, carrying out political education, showing up in solidarity. Some folks love to work behind the scenes; others want to knock on doors or marshal a demonstration. Those of us who want change need to spend less time criticizing and debating the work of other progressives. There is no such thing as a perfect action or campaign, and we learn by doing, so the best we can each do is find some like-minded folks who share our vision and get busy!

FPC: What advice would you give to anyone who wants to be an advocate for food justice?

LDP: Keep an open mind, especially when you’re new to an issue. Be prepared to learn from everyone, especially those who have experience with the problems you’re hoping to solve. Ask a lot of questions. Take notes. Read widely. Listen carefully to as many voices as you can. Then, once you have an idea worth acting on and have come up with a clear path forward, talk to everyone. Be everywhere–on social media and in print, sure, but also go to parties and chat people up, march and rally with allied organizations, offer to speak at schools, worker centers, community centers, the local yoga studio. Food justice can never occur without other kinds of justice being done, so cast a wide net.

LANA DEE POVITZ FACT SHEET

Grew up in: Montreal

City or town you call home: New York City

Job title: History professor

Background and education: McGill University (BA, MA), New York University (PhD 2017)

One word you would use to describe our food system: Wasteful

Food policy hero: Agnes Molnar

Your breakfast this morning: Pita, scrambled eggs, avocado

Favorite food: Pasta