Earlier this month, The Lancet published its 2025 Commission report on “healthy, sustainable, and just food systems” as a follow-up to its polarizing 2019 report, which was titled “Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems.” The 2025 publication marks a significant shift in the report’s political and socio-economic contextualization: the “executive summary” begins with an acknowledgment of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the increasing trend toward political instability. While The Lancet has added more culturally-inclusive language—and an initiative to make their research more culturally nuanced—the report essentially reiterates the findings of the 2019 document: we need to change the way we eat, and soon, if we want the world to be a better place. Eating healthier can help mitigate the climate emergency, but it requires a significant overhaul. The report shows our efforts to both create a just food system and save the planet are dependent on those inside and outside the food sector.

It is important to know what is inside the EAT-Lancet report because, while many people may not be aware that this program exists, it is a significant part of conversations between governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) on food and agriculture. This means the report is expected to influence what we eat over the next few decades.

Below, we have broken down the 2025 Commission report to help you better understand the discussions policy makers, scientists, scholars and businesses are having about EAT-Lancet.

What it is:

The Lancet is a weekly, peer-reviewed British medical journal. The Lancet Group, which is the organization that publishes The Lancet as well as several other specialized medical journals, claims its research reaches thousands of media outlets, policymakers and communities internationally. The Group gathers commissions of scholars and researchers to produce insights into topic-specific issues, including food and nutrition. To compile this follow-up report, they brought together a group of high-profile food industry researchers from around the world (such as Carlos A. Monteiro, who coined the term ultra-processed food and introduced the NOVA classification system).

Concerned with both physical and social improvement, the 2025 report champions a “food systems transformation” and details the targets necessary for change. Their data suggest we need to rethink how food is produced and consumed to have a healthy, sustainable planet.

As one of the achievable solutions to the climate emergency and current human health problems, for its 2019 report, the Commission created a formulaic, evidence-based diet regimen that can be replicated and scaled just about anywhere for anyone called the “Planetary Health Diet” (or PHD).

The EAT-Lancet website explains that the PHD is “a global reference diet based on the best available science. It represents a dietary pattern that supports optimal health outcomes and can be applied globally for different populations and different contexts, while also supporting cultural and regional variation.” This means that whether you were a British farm laborer or an office worker in Ho Chi Minh City, you would be able to eat the proper ratio of plant-sourced to animal-sourced foods.

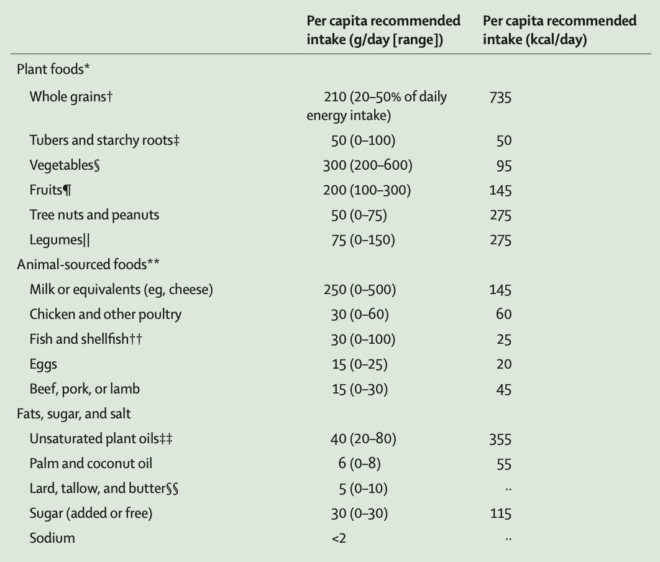

The 2025 Commission recommends broad categories of plant-sourced foods (e.g., vegetables, fruits or legumes); includes the daily percentage intakes recommended for the most popular forms of animal-sourced protein; and includes the proper amounts of popular forms of “fats, sugars, and salt”—all of which make up the “Planetary Health Diet.”

Source: “Table 1: Dietary targets for a healthy reference diet for adults, with possible ranges, for a population-level energy intake of approximately 2400 kcal/day,” from The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable, and just food systems.

The table above shows the recommended quantities and percentages of various foods you should be consuming on a daily basis to conform with the PHD. It should be noted that you are not expected to eat all of these foods every day. Rather, should you wake up today and choose to eat chicken (animal-sourced protein) and pinto beans (legumes), the Commission recommends you consume no more than 30 grams of chicken (a small breast) and 75 grams of pinto beans (one quarter of an American-size can) for the day.

Additionally, the modest portions recommended implore us to eat a diverse array of foods from the various categories. Going back to the example above, the recommended quantities of chicken and beans do not provide enough nutrients for you to reach the recommended calorie count (2400 kcal) for the day. You would also have to include servings of whole grains (brown rice) and vegetables (zucchini).

It might be a surprise to some that the Commission would consider animal-sourced protein part of a proper diet for both human and environmental health. However, the PHD is designed to be a “flexitarian” diet that is “intended to provide flexibility within a specific energy intake, with intake of animal-sourced foods not to exceed approximately two servings per day, with one being dairy… and one being non-dairy….” This means that you would be able to consume the appropriate nutrition regardless of any constraints related to your environment, cultural practices, or personal preferences. Flexitarian diets allow you to live sustainably and healthily, whether or not you choose to eat animal-sourced foods.

Many fad diets, especially in the internet age, are not supported by scientific research. The “carnivore diet” is an example of one which lacks significant evidence to prove beneficial health effects. In addition, the Commission acknowledged that the 2025 version of the PHD is “consistent with many dietary patterns, including Indigenous diets, the well-studied Mediterranean diet, and other traditional diets worldwide.” (The definitions of “Indigenous” and “traditional” remain broadly defined.)

Likewise, the report advocates for more food education. The Commission believes that “Incorporating traditional, healthy foods into national food-based dietary guidelines and nutrition education programmes can help safeguard local knowledge and culinary practices.” Initiatives like the PHD helps make more people more aware of the food systems that feed them. In fact, only a handful of universities in the United States offer higher education in programs such as Food Anthropology (as opposed to nutrition, which is a hard science), even though food is something that impacts all of us in ways we might not see explicitly.

EAT-Lancet claims that the term “Planetary Health” in the name of the diet refers to the fact that it embodies a reciprocal relationship with the Earth because “its adoption would reduce the environmental impacts and nutritional deficiencies of most current diets.” When we eat well, we, in turn, treat the planet well.

The PHD was created to conform with what the Commission calls “food system boundaries” that define the limits of safe production and consumption (i.e., how much we make and eat). Every aspect of our food systems—including, but not limited to, growing, making, processing, eating, excreting, disposing, and composting— produces various types and amounts of waste. The 2025 EAT-Lancet report predicts that the global human population will reach 9.6 billion by 2050—a growth of 23 percent since 2020—and the global GDP will increase by $282 trillion. Their data project that continuing business-as-usual (which the report shortens to “BAU”) would increase greenhouse gas emissions, require more land for agricultural use, lead to a loss of biodiversity and see a global rise in average temperature of more than 1.5ºC, among other detrimental environmental factors.

Similarly, an increase in demand for food production is directly related to an increased demand for labor. In order to produce more food, we need more labor to produce it. This means that, if the food industry continues doing business as usual, we will be perpetuating unethical practices in how our food gets to our plates. We don’t want to sacrifice human well-being for animal and environmental welfare, which is an ongoing issue and a point of contention in the plant-based food industry. You could, theoretically, eat a vegan diet that conforms to the PHD while still procuring your produce made with unpaid or forced labor. However, this would not be in line with the Commission’s larger “food systems transformation.”

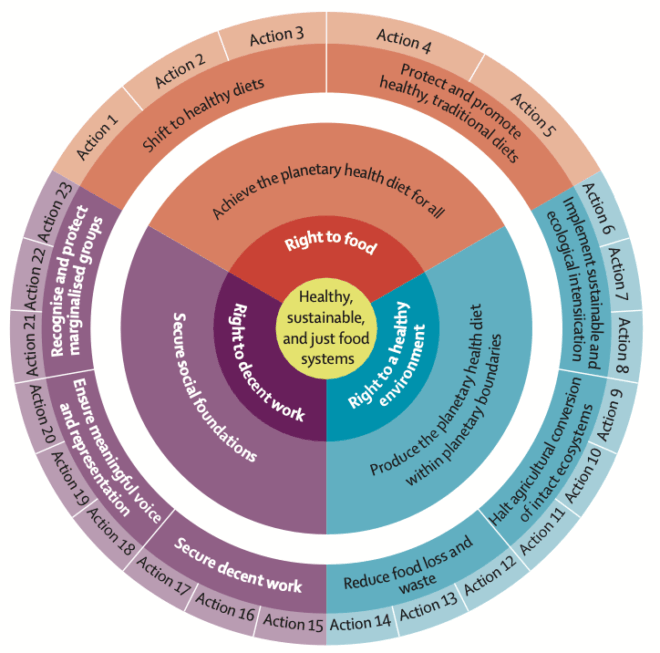

Source: “Figure 16: Goals, solutions, and actions to achieve healthy, sustainable, and just food systems,” from The EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy, sustainable, and just food systems.

Section 5 of the report imagines a three-pronged system based on: The Right to Food, The Right to Decent Work, and The Right to a Healthy Environment,some or all of which are delineated in the constitutions of various countries around the world. For example, Egypt, Guyana and Brazil all have an explicit right to food, but most countries in the Global North (i.e. hyper-industrialized nations including the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia) do not specify this kind of protection. The Commission argues the Right to Food should be something established in each country in tandem with the PHD.

“Actions” are the steps needed to achieve the right to food or decent work. Examples include: “Use taxes and subsidies to shift affordability of unhealthier foods towards the affordability of healthier foods” and “Guarantee payment of updated living wages for all and close the gender pay gap.”

An absence of advocacy for the right to food and protection in food labor trickles down to the local level. Even progressive initiatives, like New York City’s “Food Forward NYC” plan, lacks transparency for how the City’s food-industry workers are being treated in its push to provide healthy meals, increase economic opportunities and decrease carbon emissions. Nor is there any mention of the “right to food” in the plan’s two-year progress report. As far as New York politics go, New York State Senator Michelle Hinchey (D, WF) has reintroduced Senate Bill S2062 this year, which guarantees a “right to food, the right to be free from hunger, malnutrition, starvation and the endangerment of life from the scarcity of or lack of access to nourishing food.”

Most importantly, the 2025 Commission report is largely geared toward the goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement to keep the average global temperature from exceeding a 1.5ºC increase over what it was in preindustrial times, which supports the Commission’s belief, as stated in the section titled “Critical scientific assessment,” that “most emerging national food system pathways have targets that are poorly articulated, non-specific with no accountability, insufficiently ambitious, and lack appropriate financial support.” The report is intended as a means to revolutionize the food industry with an achievable goal as opposed to the vague ideal of “saving humanity.”

What it isn’t:

The 2025 EAT-Lancet report is not explicitly alarmist. While the predictive models and data presented instill concern, the Commission does not frame the report in language intended to cause panic and chaos. Its attitude is stern yet optimistic, using its own research to outline the many hurdles we will have to overcome to reverse the effects of our changing climate and global warming via our food systems.

The Commission’s matter-of-fact approach reimagining how today’s food systems will work in 2050 for a population with 1.8 billion more individuals. It implicitly indicates that if we continue consuming and wasting the way we do now, we will not have enough resources to continue living comfortably, if at all.

It is equally important to note that the 2025 report is not policy in and of itself, but intended to influence policy. The Commission’s findings are a scalable guide for local, national and international policy makers. Their goal is for many of the report’s ideals—the PHD, a massive overhaul of our food systems, better food education, as well as the right to food and decent work—to become a reality in the communities it reaches.

Controversies:

Because of the EAT-Lancet report’s ambitious nature, tall orders and sponsors, it has been the target of criticism ever since it was first released in 2019. These criticisms include its approach to class, culture, gender and race—some of which we will detail below. Researchers and scholars have highlighted the hypocrisy in the fact that the program does not offer tactical support for the equity for it advocates for. While the report may aim to establish justice in our food systems, the project itself may need more revision before policy-makers are able to implement its recommendations. In its 2025 update, the Commission has responded to and made changes in accordance with said claims.

A year after the 2019 report was released, an article in The Lancet Group’s own Global Health publication criticised the Commission for not taking into account affordability and class, implying that the cost of following the PHD would have exceeded the per-capita income of almost a quarter of the world’s population and that the diet was “more expensive than the minimum cost of nutrient adequacy….” This means even meeting the minimum 2019 PHD regimen was too expensive for billions of people, the same ones it was intended to feed.

The critique reiterates it was not food as a whole that was unaffordable for low-income individuals. The report points out malnutrition as opposed to starvation is a more pressing threat to human health. Rather the affordability and accessibility of fruits, vegetables, whole grains and fish outlined in the 2019 PHD.

The issue of cost and availability has only been exacerbated by rising food prices in the COVID and post-COVID years. This problem has become a mainstream platform for New York City’s mayoral election this year. Affordability and accessibility are part of the main focus of the 2025 report, with those words appearing all over the document. EAT-Lancet’s data suggest that the number of people who cannot afford a “healthy diet” has increased to 2.8 billion over the last five years, but states rising food prices are caused by socio-political factors as much as they are by climate change.

The report has also come into scrutiny for its apparent cultural biases. Both the 2019 and 2025 reports position themselves as initiatives to change “diet” as opposed to “cuisine.” “Diet” is defined as something along the lines of a measurable quantity of the foods you eat and “cuisine” the foods specific to a particular culture and the way they are prepared and consumed.

In 2019, under pressure from the Italian ambassador to Switzerland, Gian Lorenzo Cornado, the World Health Organization pulled out of its sponsorship of the PHD initiative. Cornado cited the negative impact of a globalized, plant-based diet on countries like Italy, whose main culinary exports include meat and dairy products—many of many of which are fundamental to Italy’s cultural heritage. While Italy’s own food sector has been criticized for its questionable advertisement of “authenticity” (e.g. DOP, IGP and STG labels) and its exploitive nature, Cornado has a point. Will a globalized, formulaic diet eliminate cultural differences the way multinational food corporations have in the past few decades? That is to say: Is the PHD mimicking the way restaurant chains like McDonald’s and KFC offer ubiquitous, predictable and engineered-to-be-tasty foods as alternatives to local cuisine?

There is an indirect response in the 2025 report to the lack of cultural nuance in 2019. Although the 2019 summary report was generally attuned to cultural differences, its examples of “healthy foods” aligned mostly with Euro-American diets: apples, spinach, avocados, cauliflower, cheese, beef, wheat, to name a few. The new document, on the other hand, ensures that the term “flexitarian” considers cultural differences as well as differences in the choices of protein sources. The Commission states the definition of a “healthy diet” not only changes from culture to culture, but also from from body to body.

In the same vein, we might worry that a shift in diet would lead to “columbusing,” or the appropriation by Western cultures of indigenous foods from around the world—a concern that arises in the wake of health fads such as the 2010s’ quinoa boom, which was accused of depriving indigenous Peruvian communities of their food sovereignty and rehashing colonial exploitative practices.

Yet another controversy revolves around an article published in 2025 in The Lancet Planetary Health journal addressing the Commission’s lack of nuance with relation to women and those assigned female at birth, particularly in terms of pregnancy and reproductive health, in the 2019 report. The article expressed concern that a decrease in animal-sourced foods would not provide sufficient nutritional value for these groups despite being beneficial for the environment.

The question of nutritional insufficiency on plant-sourced diets is addressed in the 2025 report by the Commission, stating that the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends dietary supplements (e.g. Iron or folic acid) during pregnancy. But this, of course, begs the question of whether all those who should be taking them can afford the price of expensive supplements in addition to the food in their normal diets.

Finally, the 2025 Commission recognized and addressed a massive discrepancy in the available data that can be seen as creating a cultural bias in favor of white supremacy:

In making global estimates of effects of diets on health, another general conclusion is that available data on the composition of foods, national dietary intakes, and the relation of dietary factors to health are far from optimal. Notably, large cohort studies with long follow-ups are scarce in Africa, Latin America, and most parts of Asia. Because aspects of diet strongly influence health, enhancements in data availability and quality are needed to provide better precision in future analyses and more specific regional and local dietary guidance.

This tells us how the majority of data collected comes from hyper-industrialized countries in the Global North with European, white-majority populations. This inherently links the PHD with the longstanding racist idea that Europe’s version of optimal health is everyone’s version of optimal health.

A counterargument could be that a PHD fit for Europeans would be a diet fit for anyone, as the goal of the PHD is to be scalable for any country, community or culture. Yet, this idealistic thinking runs into the same issues as stated above: it is a bold claim to say the PHD is suitable for everyone when not everyone was consulted in the creation of the diet.

It is equally problematic that The Lancet is a European publication and the 2025 Commission is comprised of researchers representing almost exclusively European and American institutions. Out of the dozens of scholars who worked on this year’s report, only nine represent institutions from Africa, Latin America and Asia. Africa has only one institution represented by the Livestock Research Institute in Ethiopia.

Finally, EAT-Lancet was funded by many donors, one being The Rockefeller Foundation, which has recently been trying to change its image with its investment in the “food as medicine” initiative. The Foundation has a long history of funding anti-wholistic medicine campaigns, because many pharmaceuticals are dependent on petrochemicals (e.g. plastics, pills, technology, etc.) from which much of the Rockefeller wealth is derived. While modern allopathic medicine is responsible for saving millions of lives, we might also see the EAT-Lancet report as a greenwashing project for the Foundation and a significant conflict of interest.

Going forward:

This article is intended to provide a broad and accessible description of what the Commission is trying to claim. It is not only important to understand what The Lancet is sharing, but also the broader socio-political context in which it exists. Immense propositions like those the Commission is advocating for do not come without pushback, both valid and invalid.

You can read the full report here.

Cover photo source: EATforum.org from https://eatforum.org/update/2025-eat-lancet-commission-launch/