By Nicholas Freudenberg, Former Faculty Director, NYC Food Policy Center at Hunter College, Distinguished Professor of Public Health, CUNY School of Public Health and Hunter College

Around the world, health professionals, nutrition researchers and food activists are recognizing that making healthy food more available and affordable, important as that is, will not by itself solve our twin problems of growing food insecurity and epidemics of diet-related diseases. We could succeed in making our neighborhoods cornucopias of fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains and other healthier foods, but if unhealthy, highly processed food with lots of sugar, salt and fat are still heavily promoted, ubiquitous and cheap, it will be hard to make improvements in health and nutrition.

As Michael Pollan, Marion Nestle and others have pointed for years, the main food message that most Americans need to hear is eat less—and differently. Despite their advertisements for healthy food, partnerships with health groups, philanthropy and corporate social responsibility, food and beverage corporations will never encourage consumers to eat less. To do so would violate their mandate to bring better returns for their investors and grow their market share.

True, food companies might offer smaller packages of unhealthy food if they think they can sell more that way, develop premium healthy products that bring higher profits, or vary the formulation of products to appeal to health conscious consumers, but never will they encourage people to eat less. To achieve that essential objective will require action from other constituencies.

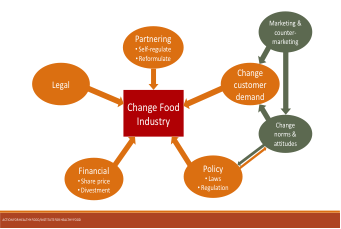

Two key players in reducing the promotion of unhealthy food are health professionals and municipal governments. The primary strategies for reducing the consumption of unhealthy foods are government regulations that limit the marketing, distribution, pricing and production of unhealthy food and public education and mobilization strategies that reduce the demand for unhealthy food. What role can health professionals and municipal governments play in these tasks?

Roles for Health Professionals

Through their clinical practice, health professionals have regular contact with a large proportion of the population. Many patients look to their providers for guidance on health and nutrition. Today big food corporations are the default nutrition educators for most Americans. Most people spend far more time watching ads for unhealthy food than they do learning about healthy eating from teachers, health educators, nutritionists or providers. What if every health professional used a fraction of the time they spend with clients to counter misleading claims from Coca Cola (Open Happiness) and McDonald’s (I’m Lovin it!)? Given the growing role of diet-related diseases in premature death and preventable illness, wouldn’t regular “immunizations” against misleading messages about food justify an investment of provider time?

Professionals can also contribute to stronger public protection against the promotion of unhealthy food by countering food industry efforts to block public health legislation. Proposals to tax soda in New York State and limit the portion size of soda containers in New York City were unsuccessful in part because the soda industry spent millions of dollars to defeat these measures. What if thousands of doctors and nurses in white coats or scrubs marched on City Hall or the State Capital to demand that legislators take action to protect their patients from a growing cause of death—diabetes and other conditions related to the rise of sugar in their diets? Or what if members of the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Cardiology threatened to quit the organization (as some have done) unless these professional societies stopped taking money from Coca Cola, the world’s largest soda company?

Finally, hospitals and health centers can make policy decisions that send a message to their communities and to policy makers. For example, no hospital should house a McDonald’s on its premises; vending machines in health facilities should not contain soda; and every health center should feature in their waiting rooms posters and videos produced by the growing number of youth-led food counter-marketing campaigns.

Roles for Municipal Governments

On October 15th, Mayors or their representatives from 100 cities signed the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact. The pact noted that cities, which now house more than half the world’s population, “have a strategic role to play in developing sustainable food systems and promoting healthy diets.” While much of the pact focused on making healthy and sustainable food more available, some of the 37 recommended action steps set the stage for reducing promotion and availability of unhealthy food. For example, the Pact called on cities to “address non-communicable diseases associated with poor diets and obesity, giving specific attention where appropriate to reducing intake of sugar, salt, trans fats, meat and dairy products and increasing consumption of fruits and vegetables and non-processed foods.”

It also encouraged municipal governments to “explore regulatory and voluntary instruments to promote sustainable diets involving private and public companies as appropriate, using marketing, publicity and labeling policies; and economic incentives or disincentives; streamline regulations regarding the marketing of food and non-alcoholic beverages to children in accordance with WHO recommendations.”

Another recommended urged cities to “support short food chains, producer organisations, producer-to-consumer networks and platforms, and other market systems that integrate the social and economic infrastructure of urban food system that links urban and rural areas. This could include civil society-led social and solidarity economy initiatives and alternative market systems. “

Finally the pact called on city governments to “review public procurement and trade policy aimed at facilitating food supply from short chains linking cities to secure a supply of healthy food, while also facilitating job access, fair production conditions and sustainable production for the most vulnerable producers and consumers, thereby using the potential of public procurement to help realize the right to food for all.

These recommendations provide a framework for city governments to define new roles in creating food systems and environments where healthy choices are easy choices and where municipal government uses its resources, mandates and authority to limit the rights of organizations and individuals to profit by encouraging products, practices and lifestyles that impose new health burdens on urban residents and new costs on their government and tax payers.

Promoting healthy food will always be easier than discouraging promotion of unhealthy food. But if we want to achieve our health and equity objectives as a city, nation and world, we’ll have to find a better way to balance these two essential goals. By exploring how health professionals and municipal governments, two of our society’s most powerful actors, can better contribute to this task, we can make progress in reducing the burden that unhealthy food imposes on our society.