In 2025, the Department of Justice conducted surprise inspections of federal prison kitchens. Inspectors found rotting produce, insect-infested storage rooms, broken refrigeration, and bread visibly covered in mold. The report shocked everyone, except the people eating the food.

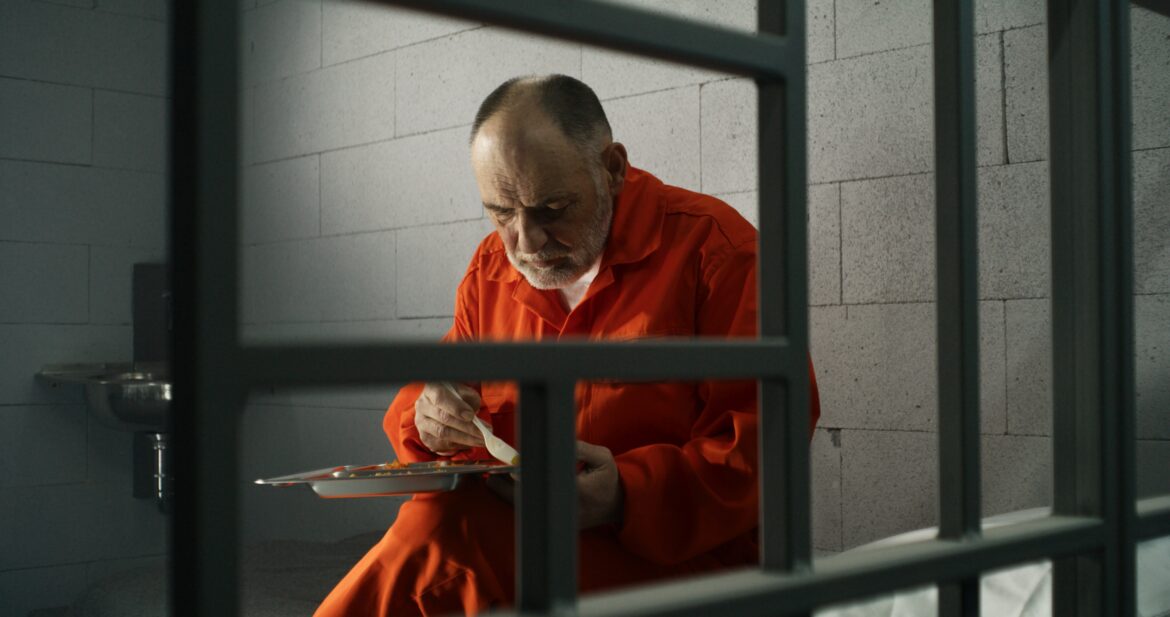

When imagining prison conditions, we often picture overcrowded cells, barbed wire perimeters, or solitary confinement; we rarely think about the food served to those incarcerated. Yet prison meals, what they contain and how they are prepared, tell us almost everything about what a society believes punishment should be. American prisons feed 1.2 million incarcerated people every day, and they do so at the lowest possible cost. Most states spend less than $3 per person per day. Some spend barely a dollar. The result: ultra-processed starches, soy-based protein fillers, sugary drinks, and kitchens so unsanitary they would be shut down if they were restaurants.

This is not accidental neglect. It is policy.

As incarceration rates skyrocketed near the end of the 20th century, particularly among poor and Black communities, states searched for ways to cut costs. Food services, labor-intensive and easy to outsource, became an early target. A handful of corporations stepped in, promising efficiency. Companies such as Aramark and Trinity Services Group now serve meals in prisons across the country and often run the commissary as well.

The commissary is an in-house store where incarcerated people can buy food, hygiene items, and other basic necessities, typically at marked-up prices. Because prison meals are frequently inadequate, many rely on it just to get enough to eat. And because the same corporations operate both the cafeteria and the commissary, they profit twice: once from the contract, and again when their own inadequate meals push people to spend money on food just to get enough to eat. At that point, food is no longer a cost to minimize. It becomes a revenue stream.

There is no federal law requiring prisons to meet specific nutritional standards, only that prisons provide “nutritionally adequate” meals, though no agency enforces what that means in practice. Without federal oversight on meal costs, calorie minimums, or nutrient requirements, states and prison administrators are left to self-regulate. The result is a patchwork of state and local policies exist in order to govern nutrition standards, but these laws lack cohesion and vary wildly in scope, detail, and enforcement. In Texas, for example, a law requires county jail inmates be fed three times a day, but this protection does not extend to state prisoners.

Oversight of food safety is equally limited. Unlike restaurants or school cafeterias, prison kitchens are rarely subject to independent health inspections. And when internal reviews do uncover problems, the findings are often hidden from the public, shielding contractors like Aramark and Trinity from accountability.

What Food Communicates

In most settings, including homes, schools, the military, and hospitals, food conveys care, identity, and belonging. In prison, food communicates the opposite. Meals are intentionally bland, colorless, and repetitive. They strip away choice and cultural identity. They send a message that says you are no longer someone whose preferences matter. Sociologists refer to this as “status degradation.”

Food is also a tool of control. In 36 states, food is allowed or required to be used as a disciplinary measure, despite the American Correctional Association urging prisons to prohibit the practice. The most notorious example is “nutraloaf,” a dense, flavorless brick of blended vegetables, starches, and beans, served in place of regular meals. It can be served at every meal for up to a week, often to those in solitary confinement. Courts have upheld its use because it meets minimal nutrition standards. But its real function is symbolic: it is edible humiliation.

Other forms of control are more subtle. To cut staffing costs, some prisons serve cold, pre-packaged breakfast items at dinner, an unappetizing swap that strips any structure or normalcy from the day. And when official meals aren’t enough to live on, incarcerated people are forced to buy food from the commissary, where prices are high, and wages paid for prison work are often pennies per hour. Many go into debt or rely on family members to send money so that they can eat adequately. The result is an environment in which mealtimes perpetuate feelings of powerlessness, dependency, and degradation.

Resistance on the Tray

Despite these conditions, food is also one of the most powerful tools of resistance inside prisons. In 2018, 1,300 people at Washington State Penitentiary refused meals, demanding better nutrition and less reliance on soy fillers. After a five day strike, the Department of Corrections agreed to serve hot oatmeal and fresh milk in place of the pre-packaged breakfasts. Others find subtler ways to reclaim agency: smuggling ingredients, improvising stoves, recreating cultural dishes that remind them who they were before incarceration.

Some take their resistance to court. The legal bar is high, but not insurmountable. The Eighth Amendment prohibits cruel and unusual punishment, and the Supreme Court has ruled that severely inadequate food can meet that threshold. Courts have also ruled against facilities that refused to provide kosher, halal, or other religiously required meals, citing federal religious freedom laws.

Whether through collective strikes, quiet cooking, or courtroom battles, these acts of resistance are about more than food. They are assertions of dignity, defying a system that treats nourishment as a privilege rather than a right.

Why It’s Time to Talk About Prison Food

Public conversation about criminal justice often focuses on sentencing reform, policing, or bail. But food, an everyday, unavoidable part of prison life, remains invisible. This silence matters. How the state nourishes, or refuses to nourish, those in its custody reveals what we truly believe about dignity, punishment, and the reach of privatization into essential government functions.

The health consequences alone should demand attention. Prisoners suffer a disproportionate number of foodborne illness outbreaks, such as Clostridium perfringens, salmonella, and norovirus. Diet-related diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes, and heart disease, are rampant in prisons. Many incarcerated individuals enter prison already at elevated risk due to the same societal inequalities that made them more vulnerable to incarceration in the first place. Prison food worsens those conditions. They leave sicker than they arrived. This is not only inhumane, it is bad public health policy. And it is avoidable.

Reforming prison food does not require reinventing the wheel. It requires political will to overcome chronic underfunding, indifference, and a privatized system in which poor-quality meals are cheaper, easier, and more profitable than change.

The solutions are straightforward: end the profit motive by bringing food services back in-house, rather than outsourcing them to corporations whose revenue increases when meals are inedible; Establish independent oversight so prison kitchens are inspected like any other public food service, subject to the same health codes as school cafeterias and hospital kitchens; raise nutritional standards beyond minimum caloric thresholds designed merely to avoid litigation; introduce autonomy where possible through communal cooking, gardens, and vocational programs that support rehabilitation rather than degradation; and invest in fresh, local, and minimally processed foods. Some facilities, such as Maine’s Mountain View Correctional Facility and Washington’s Sustainability in Prisons project, experimenting with farm-to-prison models have already shown this is both possible and cost-effective.

Talking about prison food is uncomfortable. It asks us to empathize with people many would prefer to forget. But ignoring it means accepting a system that strips dignity, punishes poverty, and enriches corporations at the expense of public health. What’s on the tray reflects the values we uphold when no one is watching. Until we fix that, we will never fix what’s broken in our prisons.